Load FindZebra Summary

Disclaimer:

FindZebra Search conducts a search using our specialized medical search engine.

FindZebra Summary uses the text completions API

(subject to OpenAI’s API data usage policies)

to summarize and reason about the search results.

The search is conducted in publicly available information on the Internet that we present “as is”.

You should be aware that FindZebra is not supplying any of the content in the search results.

FindZebra Summary is loading...

-

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 28

Orphanet

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 28 (SCA28) is a very rare subtype of type I autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA type I; see this term). ... SCA28 accounts for approximately 1.5% of all European cases of ADCA. Clinical description The mean age of symptom onset was 19.5 years in the original kindred.

-

Cataract 28

OMIM

Description Age-related cataracts are one of the leading causes of visual impairment and blindness among the elderly worldwide. Among age-related cataracts, cortical opacities rank as the second most common type (Iyengar et al., 2004). ... Few regions identified in this scan had previously been implicated in congenital or age-related cataracts. Inheritance Congdon et al. (2005) quantified the risk for age-related cortical cataract and posterior subcapsular cataract (PSC) associated with having an affected sib after adjusting for known environmental and personal risk factors. ... The model revealed that increasing age, female gender, a history of diabetes, and black race increased the odds of ARCC, whereas higher levels of provitamin A were protective. ... Pathogenesis Tan et al. (2007) studied the association of statin use with long-term incident cataract in the Blue Mountains Eye Study cohort. After controlling for age, gender, and other factors, statin use was found to reduce by 50% the risk of cataract development, principally nuclear or cortical cataract subtypes.

-

Deafness, Autosomal Dominant 28

OMIM

Affected individuals showed a mild to moderate hearing loss across most frequencies that progressed to severe loss in the higher frequencies by the fifth decade. Age at onset varied, with the earliest case documented at 7 years of age. Vona et al. (2013) studied a large 5-generation family segregating autosomal dominant postlingual hearing loss with a highly variable age of onset and progression. The proband was a man who developed bilateral progressive hearing loss at age 32 years. Hearing loss in family members with detailed clinical examination was characterized as bilateral, progressive, and usually beginning in the fifth decade of life; the youngest documented age of diagnosis was 32 years and the oldest was 65 years. ... In the proband of a large 5-generation family segregating autosomal dominant postlingual hearing loss with a highly variable age of onset and progression, who was negative for mutation in the GJB2 gene (121011) and for copy number variation, Vona et al. (2013) screened 80 known deafness-associated genes and identified a heterozygous splice site mutation in the GRHL2 gene (608576.0002) that segregated with disease in the family. ... INHERITANCE - Autosomal dominant HEAD & NECK Ears - Deafness, sensorineural - Mild to moderate hearing loss across most frequencies - Severe loss in the higher frequencies by the fifth decade MISCELLANEOUS - Variable age at onset (earliest reported 7 years) - Progressive deafness MOLECULAR BASIS - Caused by mutation in the GRHL2 gene ( 608576.0001 ) ▲ Close

-

Muscular Atrophy, Malignant Neurogenic

OMIM

Zatz et al. (1971) described a Brazilian kindred of Italian origin in which 7 members had neurogenic muscular atrophy with an unusually malignant and rapid course. Onset varied from ages 28 to 62 years and death from respiratory paralysis occurred within 1 year. ... Pulmonary - Respiratory paralysis Muscle - Neurogenic muscular atrophy Misc - Malignant and rapid course - Onset age 28 to 62 years Inheritance - Autosomal dominant ▲ Close

-

Presenile Dementia, Kraepelin Type

OMIM

In 4 of the 6 persons, onset was at a very early age: 28, 31, 33 and 34 years. Misc - Onset as early as age 28 Neuro - Nonspecific presenile dementia - Catatonia Inheritance - Autosomal dominant ▲ Close

-

Mitochondrial Complex I Deficiency, Nuclear Type 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that mitochondrial complex I deficiency nuclear type 28 (MC1DN28) is caused by homozygous mutation in the NDUFA13 gene (609435) on chromosome 19p13. ... Brain imaging in 1 patient was normal until age 7 years, when progressive cerebellar atrophy was noted. The patients were still alive at ages 12 and 5 years, although handicapped.

-

Canine Cognitive Dysfunction

Wikipedia

Pets.webmd.com . Retrieved 2014-01-28 . ^ a b Andrea Menashe (2013-10-30). ... OregonLive.com . Retrieved 2014-01-28 . ^ "Dementia (Geriatric) in Dogs" . petMD . Retrieved 2014-01-28 . ^ "Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome in Dogs" (PDF) . ... PMID 15795056 . ^ "Senior Dog Care: Older Dogs, Aged Minds: Dealing With Dog Dementia" . Drsfostersmith.com. 2013-08-26 . Retrieved 2014-01-28 .

-

Inflammatory Bowel Disease 28, Autosomal Recessive

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that inflammatory bowel disease-28 (IBD28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the IL10RA gene (146933) on chromosome 11q23. ... Begue et al. (2011) studied a French boy who had onset of perianal lesions and pancolitis with granulomas at 1 month of age. The first signs of small bowel inflammation appeared at 9 years of age, with subsequent continuous aggravation; he also developed episodes of cutaneous folliculitis as well as bronchial infections. ... Mao et al. (2012) described a 3.5-year-old Chinese boy who in the second week of life presented with fever and oral ulceration, then bloody loose stools. At 3 months of age, he had perianal ulceration, and at 6 months he continued to have bloody loose stools and perianal granulomata, as well as intermittent pyoderma. ... Analysis of IL10RA in 6 additional patients with onset of severe colitis in the first year of life revealed a homozygous missense mutation in a German patient (146933.0002); no mutations were found in 32 children with IBD who had onset of symptoms at more than 12 months of age. In a French boy who had onset of perianal lesions and pancolitis with granulomas at 1 month of age, in whom hematopoietic cells showed a lack of response to IL10, Begue et al. (2011) identified homozygosity for a missense mutation in the IL10RA gene (146933.0003).

-

Combined Oxidative Phosphorylation Deficiency 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency-28 (COXPD28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the SLC25A26 gene (611037) on chromosome 3p14. Description Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency-28 (COXPD28) is a complex autosomal recessive multisystem disorder associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. ... The children were of Iraqi, Japanese, and Moroccan descent, respectively; 2 of the families were consanguineous. The first child presented at age 4 weeks with acute circulatory collapse and pulmonary hypertension associated with severe lactic acidosis, which was successfully treated. ... The child improved, and gross development was normal until age 2 years, when she had an episode of lactic acidosis with cardiopulmonary arrest and hypoxic brain damage; afterwards she was severely handicapped. ... She had hypotonia, bradycardia, increased lactate and pyruvate, and cystic necrosis of the brain; she died at 5 days of age from respiratory and multiple organ failure.

-

Sudden Cardiac Death Of Athletes

Wikipedia

The prevalence of any single, associated condition is low, probably less than 0.3% of the population in the athletes' age group, [ citation needed ] and the sensitivity and specificity of common screening tests leave much to be desired. ... Its fatality rate is about 65% even with prompt CPR and defibrillation , and more than 80% without. [4] [5] Age 35 serves as an approximate borderline for the likely cause of sudden cardiac death. Before age 35, congenital abnormalities of the heart and blood vessels predominate. ... These athletes, in alphabetical order, experienced sudden cardiac death by age 40. Their notability is established by reliable sources in other Wikipedia articles. ... "Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research implications" . Prog Cardiovasc Dis . 51 (3): 213–28. doi : 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.003 .

-

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 11

GeneReviews

Clinical Features of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 11 View in own window Feature Number of Persons w/Feature Comment Cerebellar ataxia 28/28 Variable truncal &/or gait ataxia Limb ataxia 21/28 Dysarthria 22/28 Jerky pursuit 18/28 Nystagmus 20/28 Ophthalmoplegia 2/28 Diplopia 4/28 Hyperreflexia 18/28 Most prominent in the British family Lower > upper limbs Extrapyramidal features 1/28 Laterocollis "No-no" head tremor Onset. In the six families described with spinocerebellar ataxia type 11 (SCA11), age of onset ranged from age nine years in the family of Danish origin to age 40-50 years in the families from France, Germany, and China. ... In the Danish family, one individual presented with diplopia and nystagmus at age nine years [Lindquist et al 2017]. A sib presented at age four years with ataxia and was found to have nystagmus at age nine years [Lindquist et al 2017]. ... Life span in individuals with SCA11 is normal; many affected individuals live beyond age 75 years. In nine individuals from the British and Pakistani families, death occurred between ages 55 and 88 years.

-

Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 4c

GeneReviews

Foot deformities were first observed between ages two and ten years, were moderately or severely disabling, and required surgery in 6% (1/18) to 11% (3/28) of cases (Table 2). ... Occurrence of Manifestations of CMT4C by Study View in own window Study Finding Study (Total Patients) Azzedine et al [2006] (28) Colomer et al [2006] (14) Senderek et al [2003] (18) Houlden et al [2009] (6) Baets et al [2011] (9) Laššuthová et al [2011] (16) Yger et al [2012] (14) Fischer et al [2012] (6) Cumulative Data Age at onset 1 st symptoms 2-10 4-39 Infancy-12 1-16 <1 1-12 1-12 ND 1-16 Neuropathy 2-10 Infancy-12 1-16 <1 2-50 2-50 2-25 1-50 Age at (last) exam (yrs) 5-45 8-45 11-56 8-42 ND ND 8-59 5-59 Foot deformity Pes cavus 20/28 14/14 1 8/18 Yes ND 13/15 12/14 ND Pes planus 7/28 4/18 Yes ND no no ND Pes valgus 1/28 ND ND ND no 3/14 ND Other No Hammer toes 8/18 Small feet ND Hammer toes no ND Total 28/28 14/14 13/18 2 6/6 1 7/9 14/15 14/14 ND 96/104 (92%) Age at onset (yrs) 2-10 No data 2-12 ND ND ND 1,12 3 ND 1-12 Surgery 3/28 None 1/13 No ND 9/14 4/14 ND 17/69 (24%) Spine deformity Total 27/28 5/14 4 11/18 4 6/6 6/9 10/12 12/12 5/6 82/105 (78%) Age at onset (yrs) 2-10 4 4-12 5 ND 2, 6, 7, 12 6 ND 7-15 ND 2-15 Surgery 7 7 + 6 8 = 13/27 1/14 1/11 3/6 3/6 ND 1/12 ND 22/76 (29%) ND = not done or not documented 1. ... Authors did not indicate whether they evaluated for kyphoscoliosis and/or lordosis. 5. Onset of scoliosis in infancy; age not reported 6.Age documented in 4 patients only 7. ... Additional Clinical Findings in CMT4C by Study View in own window Clinical Finding Study (Total Patients) Azzedine et al [2006] (28) Colomer et al [2006] (14) Senderek et al [2003] (18) Houlden et al [2009] (6) Baets et al [2011] (9) Laššuthová et al [2011] (16) Yger et al [2012] (14) Cumulative Data Hypoacusis 5/28 0/14 2/18 0/6 0/9 0/15 8/13 15/103 Deafness 0/28 5/14 1/18 2/6 1/9 3/15 0/13 12/103 Nystagmus 0/28 0/14 2/18 0/6 2/9 0/15 0/13 4/103 Pupillary light reflexes 0/28 3/14 0/18 1/6 0/9 0/15 14/13 4/20 Other pupillary disturbances -- -- -- Asymmetric size 1/6 -- -- -- 1/6 Lingual fasciculation -- 3/14 -- -- -- -- -- 3/14 Tongue atrophy and/or weakness -- -- -- 1/6 -- -- 2/13 3/19 Facial paresis 1/28 -- -- 1/6 1/9 -- 4/13 7/56 Facial weakness -- -- -- 1/6 -- -- -- 1/6 Head tremor -- 2/14 -- -- -- -- -- 2/14 Vocal cord involvement -- -- -- -- -- -- 1/13 1/13 Total patients w/cranial nerve involvement 5/28 9/14 5/14 1 4/6 -- -- 10/13 33/73 Respiratory insufficiency or hypoventilation 7/28 2 -- 2/18 -- 1/9 -- -- 10/55 Sensory ataxia 1/28 2/14 -- -- -- -- -- >3/42 3 Diabetes mellitus -- -- 1/18 -- -- -- -- 1/18 Romberg sign -- 2/14 -- -- -- -- -- 2/14 1. 14 of 18 patients were examined for cranial nerve involvement. 2. ... They also reported intrafamilial variability in age at onset, disease duration, and stage of disability.

-

Lucio And Simplicio Godina

Wikipedia

Lucio and Simplicio Godina Born March 8, 1908 Samar , Philippines Died Lucio: 24 November 1936 (1936-11-24) (aged 28) Simplicio: 8 December 1936 (1936-12-08) (aged 28) New York City , U.S. Spouse(s) Lucio: Natividad Matos Simplicio: Victorina Matos (Natividad and Victorina Matos were identical twin sisters ) Lucio Godina (March 8, 1908 – November 24, 1936) and Simplicio Godina (March 8, 1908 - December 8, 1936) were pygopagus conjoined twins from the island of Samar in the Philippines . At the age of 21 they married Natividad and Victorina Matos, who were identical twins .

-

Epileptic Encephalopathy, Early Infantile, 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-28 (EIEE28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the WWOX gene (605131) on chromosome 16q23. ... Clinical Features Abdel-Salam et al. (2014) reported an Egyptian girl, born of consanguineous parents, with a severe lethal neurologic phenotype resulting in death at age 16 months. At age 3 months, the patient had microcephaly (-3.6 SD), poor growth, and lack of psychomotor development. She developed intractable seizures at age 2 months. She had myoclonic movements and hyperreflexia as well as optic atrophy with retinal dysfunction. ... She was 1 of twins; the other twin was unaffected and heterozygous for the mutation. An older sib had died at age 3 months of a similar disorder. That sib developed seizures at age 40 days and did not follow objects or react to light, suggesting retinal degeneration. ... All patients developed pharmacoresistant focal, multifocal, or generalized seizures at a median age of 2 months. All had profoundly delayed psychomotor development; 2 had progressive microcephaly.

-

Dystonia 28, Childhood-Onset

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that childhood-onset dystonia-28 (DYT28) is caused by heterozygous mutation in the KMT2B gene (606834) on chromosome 19p13. Description Dystonia-28 is an autosomal dominant neurologic disorder characterized by onset of progressive dystonia in the first decade of life. ... There were no additional motor neurologic features, and brain imaging was normal in all 4 probands. The oldest proband (family F1), aged 31 years, underwent deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus with improvement of her condition. ... Meyer et al. (2017) reported 17 probands, ranging in age from 6 to 40 years, with childhood-onset dystonia. All patients had onset of symptoms in the first decade, except for a 46-year-old affected mother who reportedly had onset at age 23 years; her son had onset at age 8 years.

-

Deafness, Autosomal Dominant 27

OMIM

All affected individuals exhibited nonsyndromic bilateral progressive sensorineural hearing loss. The reported age of onset in the 11 affected individuals ranged from 7 to 28 years. Affected individuals under the age of 40 years exhibited moderate to profound hearing loss (40- to 90-decibel loss), whereas older affected individuals had severe to profound hearing loss. ... INHERITANCE - Autosomal dominant HEAD & NECK Ears - Hearing loss, progressive bilateral sensorineural, moderate-to-profound MISCELLANEOUS - Age of onset varies (7 to 28 years of age) - Based on one large North American family (last curated August 2015) ▲ Close

-

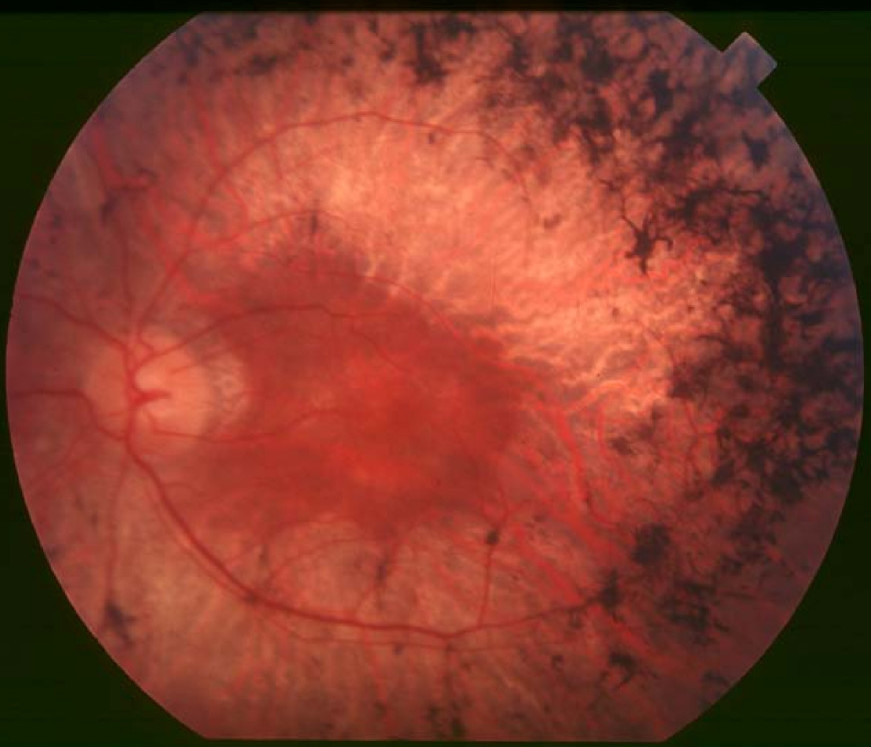

Retinitis Pigmentosa 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because retinitis pigmentosa-28 (RP28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the FAM161A gene (613596) on chromosome 2p15. ... Clinical Features Gu et al. (1999) described a consanguineous Indian family in which 4 members in 2 generations had autosomal recessive RP. Age of onset was between 5 and 15 years. The 3 oldest members, aged 39 to 47, had severe visual handicap. ... The course of the disease is rather slow, with age of onset in the second or third decade, severe visual handicap in the fifth decade, and legal blindness in the sixth to seventh decades. However, the youngest Indian patient had early onset of disease, at 5 years of age, and more rapid progression, with a visual acuity at age 15 of 3/60 in the left eye and the right eye reduced to counting fingers.C8orf37, PDE6B, PDE6A, CRX, RPGR, RPE65, PDE6G, LRAT, ABCA4, EYS, MERTK, IMPDH1, ROM1, RHO, USH2A, CRB1, CNGB1, RPGRIP1, GUCY2D, RP2, NRL, RBP3, CLRN1, RDH12, SAG, SPATA7, CNGA1, ARL6, AIPL1, REEP6, RGR, DHX38, GUCA1B, OFD1, IDH3A, IDH3B, PRPF8, RP1, FAM161A, TULP1, SNRNP200, PRPF31, CERKL, NR2E3, CA4, MAK, PRCD, PRPF3, RLBP1, PROM1, PCARE, CHM, ARL2BP, TOPORS, BBS1, CYP4V2, BEST1, DHDDS, KLHL7, IMPG2, HGSNAT, IFT140, PRPF6, BBS2, TTC8, AHI1, SCAPER, CLN3, IFT172, CDHR1, KIZ, FLVCR1, TTPA, ARL3, PRPF4, AGBL5, RP9, SLC7A14, FSCN2, POMGNT1, ZNF513, ZNF408, RBP4, ABHD12, UNC119, NEK2, AHR, TUB, SEMA4A, ATF6, IFT88, FOXI2, UBAP1L, CCZ1B, CROCC, PDAP1, FAM71A, KIAA1549, IRX5, ARHGEF18, C1QTNF5, PRTFDC1, SLC37A3, NAALADL1, CRB2, NGF, CEP250, CWC27, CCDC66, GRIN2B, PRPH2, AGTPBP1, SLC6A6, AIFM1, FGFR2, KL, MT2A, PTEN, MYO7A, CEP290, GUCA1A, RDH5, CDH23, IQCB1, MSTO1, CACNA1A, BBS4, ATXN7, USH1C, CFAP410, ATP6, PANK2, MKKS, BBS9, SLC24A1, PEX1, RP1L1, HADHA, PNPLA6, SDCCAG8, BBS12, NDUFAF5, RRM2B, PDHA1, NDUFS8, NDUFV2, LZTFL1, FOXRED1, POMT2, RCBTB1, TST, FKRP, BBS7, CNGB3, NCAPG2, NPHP1, MKS1, NDUFB11, SURF1, SDHB, PEX2, WDPCP, PRPH, NDUFV1, NDUFA13, SCN1A, SCO1, SDHA, SDHD, PHYH, TACO1, LIPT1, SLC19A1, NDUFA12, PEX5, NGLY1, ALMS1, LARGE1, NDUFS4, PRDX1, NDUFS3, POLR3A, MFSD8, ZDHHC24, RNASEH1, CTNS, ARL13B, TRIM32, NIPAL1, ECHS1, FASTKD2, ERCC3, POMT1, ERCC6, ERG, IFT27, NDUFAF6, BBS5, NDUFS2, CLRN1-AS1, COX20, CYGB, COX15, COX10, COX8A, COX7B, CDH23-AS1, ACOX1, C8orf37-AS1, MMACHC, JAG1, AMACR, AIRE, PET100, SDHAF1, ZFYVE26, PHF3, ATP1A2, BCS1L, NDUFS7, CAV1, TTLL5, VSX2, ERCC8, COX6B1, PRRT2, MTFMT, GSS, COL18A1, GMPPB, HADHB, ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND5, ND6, TRNK, TRNL1, TRNN, TRNS1, TRNV, TRNW, TRIM37, BBS10, NDUFA2, NDUFA4, NDUFA9, NDUFA10, NDUFS1, SLC19A3, WFS1, BBIP1, COA8, HCCS, NDUFAF2, HADH, TMEM14B, COX14, PLXNA2, LSM2, TRNT1, CLU, MFRP, PCDH15, DHX16, PTPRC, SLU7, KLK3, SIGMAR1, NXNL1, CLTA, CNTF, NT5C2, RPE, PROS1, PLAG1, NPHP4, TIMP3, PSAT1, NPEPPS, MYP2, CXCR6, RIMS1, RRH, SLC19A2, EXOSC2, ADIPOR1, LPAR2, USP9X, COG4, VCP, EDN1, LCA5, PDC, ATN1, OTX2, OTC, CNOT3, MVK, LPCAT1, MMP9, EDNRA, RCC1, EPO, INS, FANCF, HSPA4, HK1, GNAT1, HIF1A, OPN4, GSN, SERPINF1, GPR42, NSMCE3, GRK1, ALDH3A2, SFRP2, ACKR3, ADRA1A, ARL2, ATXN2, CC2D2A, ADRA2B, WDR19, SOD3, PLIN2, SSTR4, BRS3, STC1, ACTB, NRG4, TWIST2, GRK7, POC5, ARMS2, MFT2, SAMD11, SAMD7, NOC2L, JAKMIP1, MIR204, POLDIP2, GUCY2EP, LIN28B, NPHP3, ARSI, RD3, CENPV, PITPNM3, INVS, CENPK, TENT5A, CYCS, DCUN1D1, TWNK, SLC2A4RG, TBX20, RDH11, PNPLA2, KIDINS220, NGB, MPP4, NYX, TNMD, ENFL2, TUT1, DNER, FTO, ELOVL6, ALG12, RNF19A, COQ8B, SETD2, KLF15, PDZD7, HKDC1, C5AR2, DNAJC17, ADGRV1, CEP78, GNPTG, AAVS1, THBS2, WHRN, MMP2, HMOX1, HK2, HGF, GRM5, GRM1, GRB10, GLO1, GK, GJB2, GDNF, GDF2, G6PD, FRZB, FN1, FGF5, FGF2, FBN2, HSP90AA1, IDH2, IFNG, INSR, MEIS2, MDH1, MAP1A, SMAD4, LTB, LAMP1, ISG20, ING1, IGF1, IMPA1, CXCL8, IL6, IL2RA, IL1B, IL1A, CCN1, FASN, ETV5, ERN1, ALDH7A1, CACNA1F, C5AR1, C3, C1QBP, BSG, BMP4, BCL2, ARRB2, CANX, ARR3, ABCC6, APOE, APOB, AMFR, ADH7, ABO, CACNA1S, CCT, ERBB2, CYBB, EGF, E2F1, DUSP6, DNMT3A, CFD, ACE, CYLD, CTNNB1, CD44, MAPK14, CRYAB, CRK, CP, CORD1, COL2A1, CD74, RAB8A, MSR1, SH3BP4, CYTB, SYNJ1, FGF18, HSD17B6, DGKE, BRAP, SMC1A, USP11, AIMP2, PAX8, ZNF132, ZFP36, USH1E, TSC1, TP53, TNF, TMPRSS2, TSPAN7, SMC3, ARHGEF2, CRLF1, AKT3, TMED3, SIRT1, ARC, MAPRE3, ARPP21, AHSA1, PPIH, HEPH, SNAP29, PLEKHM1, PHYHIP, HDAC4, KNTC1, EIF2AK3, GRAP2, EFTUD2, TIMP2, TIMP1, DYNLT3, PKNOX1, HTRA1, PRNP, MAPK1, PRKCG, POLG, PMM2, PLAU, PIM1, RAC1, PGF, CFP, PDGFRB, NPTX2, NFE2L2, NAGLU, MYC, ALDH18A1, RASGRF1, ELOVL4, SFTPD, STATH, SOS1, SOD1, SNRPB, SNCA, SLC2A1, SGSH, SFRP5, RBP1, SEC14L1, CX3CL1, CCL2, S100A6, RPS6KB1, RPS6, RCVRN, H3P22

-

Spermatogenic Failure 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because of evidence that spermatogenic failure-28 (SPGF28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the FANCM gene (609644) on chromosome 14q21. Description Spermatogenic failure-28 is characterized by nonobstructive azoospermia, with a Sertoli cell-only phenotype observed in testicular tissue (Kasak et al., 2018). ... Clinical Features Kasak et al. (2018) studied 2 Estonian brothers, aged 26 and 29 years, who had been diagnosed with idiopathic nonobstructive azoospermia.

-

Abortion In Nepal

Wikipedia

In fact about 20% of women prisoners were imprisoned for abortion-related choices. [6] According to the law women had access to legal abortion only under the following conditions · The pregnancy must be under 12 weeks of gestation. If the woman is above 16 years of age, she does not require the permission of her husband or her guardian. · In the case of rape or incest, the pregnancy must be under 18 weeks of gestation. · If recommended by the doctor, at any stage of the pregnancy if it poses danger to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or if the foetus suffers from severe physical deformity. [7] References [ edit ] ^ Worrell, Marc. ... Women on Waves . Retrieved 2018-09-28 . ^ Bhandari, T. R.; Dangal, G. (2015-08-17). ... PMID 28825899 . ^ "Vacuum Aspiration for Abortion | CS Mott Children's Hospital | Michigan Medicine" . www.mottchildren.org . Retrieved 2018-09-28 . ^ "10 Things You Should Know about Abortion Service in Nepal" . The ASAP Blog . 2015-08-24 . Retrieved 2018-09-28 . ^ Wu, Wan-Ju; Maru, Sheela; Regmi, Kiran; Basnett, Indira (June 2017). ... Women on Waves . Retrieved 2018-09-28 .

-

Immunodeficiency 28

OMIM

A number sign (#) is used with this entry because immunodeficiency-28 (IMD28) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the IFNGR2 gene (147569) on chromosome 21q22. ... Both parents and 1 of 2 sibs were heterozygous for the mutation, but they did not develop disease. The affected child died at age 5 years of disseminated M. avium disease in spite of treatment with multiple antimycobacterial drugs.