Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a type of muscular dystrophy that preferentially weakens the skeletal muscles of the face (Latin: facio), those that position the scapula (scapulo), and those in the upper arm, overlying the humerus bone (humeral). Weakness of the scapular muscles causes an abnormally positioned scapula (winged scapula). Other areas of the body usually develop weakness as well, such as the abdomen and lower leg, causing foot drop. The two sides of the body are often affected unequally. Symptoms typically begin in early childhood and become noticeable in the teenage years, with 95% of affected individuals manifesting disease by age 20 years. Non-muscular manifestations of FSHD include hearing loss and blood vessel abnormalities in the back of the eye.

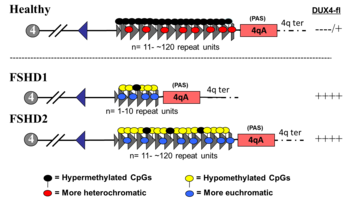

FSHD is caused by complex genetic changes involving the DUX4 gene. In those without FSHD, DUX4 is expressed (ie: turned on) in early human development and later repressed (ie: turned off) in mature tissues. In FSHD, DUX4 is inadequately turned off, which can be caused by several different mutations, the most common being deletion of DNA in the region surrounding DUX4. This mutation is termed "D4Z4 contraction" and defines FSHD type 1 (FSHD1), making up 95% of FSHD cases. FSHD due to other mutations is classified as FSHD type 2 (FSHD2). Regardless of which mutation is present, disease can only result if the individual has a 4qA allele, which is a common variation in the DNA next to DUX4. Up to 30% of FSHD cases are due to a new mutation, which then is able to be passed on to children. FSHD1 follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning each child of an affected individual has a 50% chance of also being affected. How DUX4 expression causes muscle damage is unclear. Expression of DUX4 gene produces DUX4 protein, whose function is to modulate hundreds of other genes, many of which are involved in muscle function. Diagnosis is by genetic testing.

There is no known cure for FSHD. No pharmaceuticals have proven effective for altering the disease course. Symptoms can be addressed with physical therapy, bracing, and reconstructive surgery. Surgical fixation of the scapula to the thorax is effective in reducing shoulder symptoms in select cases. FSHD is the third most common genetic disease of skeletal muscle (Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy being first and myotonic dystrophy being second), affecting 1 in 8,333 to 1 in 15,000 people. Prognosis is extremely variable, with many never facing significant limitations, although up to 20% of affected individuals become severely disabled, requiring use of a wheel chair or mobility scooter. Life expectancy is generally not affected, except in rare cases of respiratory insufficiency.

The first description of an individual with FSHD is an autopsy report from 1852, although FSHD wasn't distinguished as a disease until the 1870s and 1880s when French physicians Landouzy and Dejerine followed a family affected by it; thus FSHD is sometimes referred to as Landouzy–Dejerine muscular dystrophy. In 1991, the association of most cases with the tip of chromosome 4 was established, which was discovered to be due to D4Z4 contraction in 1993. DUX4 was discovered in 1999, but it wasn't until 2010 that the genetic mechanism causing its expression was elucidated. In 2012, the predominant mutation of FSHD2 was discovered. In 2014, researchers published the first proposed pathophysiology definition of the disease and four viable therapeutic targets for possible intervention points.

Signs and symptoms

Muscles of the face, shoulder girdle, and upper arm are classically affected, although these muscles can be spared and other muscles usually are affected. Distribution and degree of muscle weakness is extremely variable, even between identical twins. Individual muscles can weaken while adjacent muscles remain healthy. Muscle weakness usually becomes noticeable on one side of the body before the other, a hallmark of the disease. The right shoulder muscles are more often affected than the left shoulder muscles, independent of handedness.:139 Musculoskeletal pain is very common, most often described in the neck, shoulders, lower back, and the back of the knee. Classically, symptoms appear in those 15 – 30 years of age, although infantile onset, adult onset, and absence of symptoms despite having the causal genetics also occur. Long static phases, in which no progression is apparent, is not uncommon. FSHD1 and FSHD2 have similar signs and symptoms, although very large D4Z4 deletions in FSHD1 (EcoRI 10-11 kb) are more strongly associated with infantile onset, progressive hearing loss, retinal disease, and various rare manifestations.

Face and shoulder

Weakness typically begins in the muscles of the face. At least mild facial weakness can be found in 90% or more with FSHD, although it is rarely the initial complaint. The muscles surrounding the eyes (orbicularis oculi muscle) are commonly affected, which can result in sleeping with eyelids open. The muscle surrounding the mouth (orbicularis oris muscle) is also commonly affected, resulting in inability to pucker the lips or whistle. There can be difficulty pronouncing the letters M, B, and P, or facial expressions that appear diminished, depressed, angry, or fatigued. After the facial weakness, weakness usually develops in the muscles of the upper torso, especially those connecting shoulder girdle to the thorax. Weakness of the shoulder girdle muscles is the initial complaint in 80% of cases, and the disease doesn't progress further in 30% of familial cases. Predominantly, the serratus anterior muscle and middle and lower trapezius fibers are affected; the upper trapezius fibers often are spared.. This weakness causes the scapulas to become downwardly rotated and protracted, resulting in winged scapulas, horizontal clavicles, and sloping shoulders. In advanced cases, the scapula appears to "herniate" up and over the rib cage. A common complaint is difficulty working with the arms overhead. The rotator cuff muscles are usually spared, even late in the disease course. Another commonly affected upper torso muscle is the pectoralis major muscle, particularly the sterno costal portion, atrophy of which can contribute to a prominent horizontal anterior axillary fold.

Upper arm and lower body

After facial and upper torso weakness, weakness can "descend" to the upper arms (biceps muscle and triceps muscle) and the pelvic girdle. The forearms are usually spared, resulting in an appearance some compare to the fictional character Popeye. Sometimes, the weakness is observed to "skip" the pelvis and involve the tibialis anterior (shin muscle), causing foot drop. Weakness can also occur in the abdominal muscles, which can manifest as a protuberant abdomen, lumbar hyperlordosis, the inability to do a sit-up, or the inability to turn from one side to the other while lying down. The lower fibers of the rectus abdominis muscle are more often affected than the upper fibers, manifesting as a positive Beevor's sign. Weakness in the legs can manifest as difficulty walking or hips held in slight flexion.

Muscle involvement from medical imaging perspective

Medical imaging (CT and MRI) has shown muscle damage that doesn't cause obvious symptoms. A single MRI study shows the teres major muscle to be commonly affected. The semimembranosus muscle, part of the hamstrings, is commonly affected, with one author stating it to be "the most frequently and severely affected muscle." Also, MRI shows that the rectus femoris is more often affected than the other muscles of the quadriceps, the medial gastrocnemius is more often affected than the lateral gastrocnemius, and the iliopsoas muscle is very often spared.

Non-musculoskeletal

The most common non-musculoskeletal manifestation of FSHD is mild retinal blood vessel abnormalities, such as telangiectasias or microaneurysms, with one study placing the incidence at 50%. These abnormal blood vessels generally do not affect vision or health, although a severe form of it mimics Coat's disease, a condition found in about 1% of FSHD cases and more frequently associated with large 4q35 deletions. High-frequency hearing loss can occur in those with large 4q35 deletions, but otherwise is no more common compared to the general population. Breathing can be affected, associated with kyphoscoliosis and wheelchair use; it is seen in one-third of wheelchair-bound patients. However, ventilator support (nocturnal or diurnal) is needed in only 1% of cases.

Genetics

The genetics of FSHD are complex, culminating in abnormal expression of the DUX4 gene. In those without FSHD, DUX4 is expressed during embryogenesis and, at some point, becomes repressed in all tissues except the testes. In FSHD, there is inadequate repression of DUX4, allowing ectopic production of DUX4 protein in muscles, causing muscle damage. Two genetic elements are required for inadequate repression of DUX4. First, there must be a mutation that causes hypomethylation of the DNA surrounding DUX4, allowing transcription of DUX4 into messenger RNA (mRNA). Several mutations cause hypomethylation, upon which FSHD is subclassified into FSHD type 1 (FSHD1) and FSHD type 2 (FSHD2).

The second genetic element needed is a polyadenylation sequence downstream to DUX4 that allows stability to DUX4 mRNA, which allows DUX4 mRNA to persist long enough to be translated into DUX4 protein, the causal agent of muscle damage. There are at least 17 variations, or haplotype polymorphisms, of 4q35 (DNA encompassing D4Z4 repeat array) observed in the population. These 17 variations can be roughly divided into the groups 4qA and 4qB. It are the 4qA alleles that contain polyadenylation signals, allowing stability to DUX4 mRNA. The 4qB alleles do not have polyadenylation sequences.

DUX4 and the D4Z4 repeat array

| CEN | centromeric end | TEL | telomeric end |

| NDE box | non-deleted element | PAS | polyadenylation site |

| triangle | D4Z4 repeat | trapezoid | partial D4Z4 repeat |

| white box | pLAM | gray boxes | DUX4 exons 1, 2, 3 |

| arrows | |||

| corner | promoters | straight | RNA transcripts |

| black | sense | red | antisense |

| blue | DBE-T | dashes | dicing sites |

DUX4 resides within the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array, a series of tandemly repeated DNA segments in the subtelomeric region (4q35) of chromosome 4. Each D4Z4 repeat is 3.3 kilobase pairs (kb) long and is the site of epigenetic regulation, containing both heterochromatin and euchromatin structures. In FSHD, the heterochromatin structure is lost, becoming euchromatin. The name "D4Z4" is derived from an obsolete nomenclature system used for DNA segments of unknown significance during the human genome project: D for DNA, 4 for chromosome 4, Z indicates it is a repetitive sequence, and 4 is a serial number assigned based on the order of submission.

DUX4 consists of three exons. Exons 1 and 2 are in each repeat. Exon 3 is in the pLAM region telomeric to the last partial repeat. Multiple RNA transcripts are produced from the D4Z4 repeat array, both sense and antisense. Some transcripts might be degraded in areas to produce si-like small RNAs. Some transcripts that originate centromeric to the D4Z4 repeat array at the non-deleted element (NDE), termed D4Z4 regulatory element transcripts (DBE-T), could play a role in DUX4 derepression. One proposed mechanism is that DBE-T leads to the recruitment of the trithorax-group protein Ash1L, an increase in H3K36me2-methylation, and ultimately de-repression of 4q35 genes.

FSHD1

FSHD involving deletion of D4Z4 repeats (termed 'D4Z4 contraction') is classified as FSHD1, which accounts for 95% of FSHD cases. Typically, chromosome 4 includes between 11 and 150 repetitions of D4Z4. In FSHD1, there are 1–10 repetitions of D4Z4. The number of repeats roughly inversely correlates with disease severity. Namely, those with 1 - 3 repeats are more likely to have severe, atypical, and early onset disease; those with 4 - 7 repeats have moderate disease that is highly variable; and those with 8 - 10 repeats tend to have the mildest presentations, sometimes with no symptoms. D4Z4 contraction causes D4Z4 hypomethylation, allowing DUX4 transcription. Deletion of the entire D4Z4 repeat array does not result in FSHD because then there are no complete copies of DUX4 to be expressed, although other birth defects result. Inheritance is autosomal dominant, although 10 - 30% of cases are from de novo (new) mutations.

The subtelomeric region of chromosome 10q contains a tandem repeat structure highly homologous (99% identical) to 4q35. The repeats of 10q are termed "D4Z4-like" repeats. Because 10q usually lacks a polyadenylation sequence, it is generally not implicated in disease, except in the instance of chromosomal rearrangements between 4q and 10q leading to 4q D4Z4 contraction, or the other instance of transfer of a 4q D4Z4 repeat and polyadenylation signal onto 10q.

It has been posited that FSHD1 undergoes anticipation, a phenomenon classically associated with trinucleotide repeat disorders in which disease manifestation worsens with each subsequent generation. As of 2019, more detailed studies are needed to definitively show whether or not anticipation plays a role. If anticipation does occur in FSHD, the mechanism is different than that of trinucleotide repeat disorders, since the D4Z4 repeats are not trinucleotide repeats, and the repeat array size in FSHD is stable across generations.

FSHD2

FSHD without D4Z4 contraction is classified as FSHD2, which constitutes 5% of FSHD cases. Various mutations cause FSHD2, all resulting in D4Z4 hypomethylation, at which the genetic mechanism converges with FSHD1. Approximately 80% of FSHD2 cases are due to deactivating mutations in the gene SMCHD1 (structural maintenance of chromosomes flexible hinge domain containing 1) on chromosome 18. SMCHD1 is responsible for DNA methylation, and its deactivation results in hypomethylation of the D4Z4 repeat array. Another cause of FSHD2 is mutation in DNMT3B (DNA methyltransferase 3B), which also plays a role in DNA methylation. As of 2020, early evidence indicates that a third cause of FSHD2 is mutation in both copies of the LRIF1 gene, which encodes the protein ligand-dependent nuclear receptor-interacting factor 1 (LRIF1). LRIF1 is known to interact with the SMCHD1 protein. As of 2019, there are presumably additional mutations at other unidentified genetic locations that can cause FSHD2.

Mutation of a single allele of SMCHD1 or DNMT3B can cause disease. Mutation of both copies LRIF1 has been tentatively shown to cause disease in a single person as of 2020. As in FSHD1, a 4qA allele must be present for disease to result. However, unlike the D4Z4 array, the genes implicated in FSHD2 are not in proximity with the 4qA allele, and so they are inherited independently from the 4qA allele, resulting in a digenic inheritance pattern. For example, one parent without FSHD can pass on an SMCHD1 mutation, and the other parent, also without FSHD, can pass on a 4qA allele, bearing a child with FSHD2.

Two ends of a disease spectrum

Initially, FSHD1 and FSHD2 were described as two separate genetic causes of the same disease. However, they can also be viewed not as distinct causes, but rather as risk factors. Not rarely do both contribute to disease in the same individual.

In those with FSHD2, although they have do not have a 4qA allele with D4Z4 repeat number less than 11, they still often have one less than 17 (relatively short compared to the general population), suggesting that a large number of D4Z4 repeats can prevent the effects of an SMCHD1 mutation. Further studies need to be done to determine the upper limit of D4Z4 repeats in which FSHD2 can occur.

In those with a 4qA allele and 10 or fewer repeats, an additional SMCHD1 mutation has shown to worsen disease, classifying them as both FSHD1 and FSHD2. In these FSHD1/FSHD2 individuals, the methylation pattern of the D4Z4 repeat array resembles that seen in FSHD2. This combined FSHD1/FSHD2 presentation is most common in those with 9 - 10 repeats, and is seldom found in those with 8 or less repeats. The relative abundance of SMCHD1 mutations in the 9 - 10 repeat group is likely because a sizable portion of the general population has 9 - 10 repeats with no disease, yet with the additive effect of an SMCHD1 mutation, symptoms develop and a diagnosis is made. In those with 8 or fewer repeats, symptoms are more likely than in those with 9 - 10 repeats, leading to diagnosis regardless of an additional SMCHD1 mutation.

The apparent frequency of FSHD1/FSHD2 cases in the 9 - 10 repeat range, combined with the FSHD2-like methylation pattern, suggest the 9 - 10 repeat size to be an overlap zone between FSHD1 and FSDH2.

Pathophysiology

As of 2020, there seems to be a consensus that aberrant expression of DUX4 in muscle is the cause of FSHD. DUX4 is expressed in extremely small amounts, detectable in 1 out of every 1000 immature muscle cells (myoblast), which appears to increase after myoblast maturation, in part because the cells fuse as they mature, and a single nucleus expressing DUX4 can provide DUX4 protein to neighboring nuclei from fused cells.

It remains an area of active research how DUX4 causes muscle damage. DUX4 protein is a transcription factor that regulates many other genes. Some of these genes are involved in apoptosis, such as p53, p21, MYC, and β-catenin. It seems that DUX4 makes muscle cells more prone to apoptosis, although details of the mechanism are still unknown and contested. Other DUX4 regulated genes are involved in oxidative stress, and it seems that DUX4 expression lowers muscle cell tolerance of oxidative stress. Variation in the ability of individual muscles to handle oxidative stress could partially explain the muscle involvement patterns of FSHD. DUX4 downregulates many genes involved in muscle development, including MyoD, myogenin, desmin, and PAX7. DUX4 has shown to reduce muscle cell proliferation, differentiation, and fusion. Estrogen seems to play a role on in modifying DUX4 effects on muscle differentiation, which could explain why females are less affected than males. DUX4 regulates a few genes that are involved in RNA quality control, and DUX4 expression has been shown to cause accumulation of RNA with subsequent apoptosis.

The cellular hypoxia response has been reported in a single study to be the main driver of DUX4-induced muscle cell death. The hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are upregulated by DUX4, possibly causing pathologic signaling leading to cell death.

Another study found that DUX4 expression in muscle cells led to the recruitment and alteration of fibrous/fat progenitor cells, which helps explain why muscles become replaced by fat and fibrous tissue.

Diagnosis

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is the gold standard for FSHD diagnosis, as it is the most sensitive and specific test available. Commonly, FSHD1 is tested for first. A shortened D4Z4 array length (EcoRI length of 10 kb to 38 kb) with an adjacent 4qA allele supports FSHD1. If FSHD1 is not present, commonly FSHD2 is tested for next by assessing methylation at 4q35. Low methylation (less than 20%) in the context of a 4qA allele is sufficient for diagnosis. The specific mutation, usually one of various SMCHD1 mutations, can be identified with next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Assessing D4Z4 length

Measuring D4Z4 length is technically challenging due to the D4Z4 repeat array consisting of long, repetitive elements. For example, NGS is not useful for assessing D4Z4 length, because it breaks DNA into fragments before reading them, and it is unclear from which D4Z4 repeat each sequenced fragment came. In 2020, optical mapping became available for measuring D4Z4 array length, which is more precise and less labor intensive than southern blot. Molecular combing is also available for assessing D4Z4 array length. Sometimes 4q or 10q will have a combination of D4Z4 and D4Z4-like repeats due to DNA exchange between 4q and 10q, which can yield erroneous results, requiring more detailed workup.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was the first genetic test developed and is still used as of 2020, although it is being phased out by newer methods. It involves dicing the DNA with restriction enzymes and sorting the resulting restriction fragments by size using southern blot. The restriction enzymes EcoRI and BlnI are commonly used. EcoRI isolates the 4q and 10q repeat arrays, and BlnI dices the 10q sequence into small pieces, allowing 4q to be distinguished. The EcoRI restriction fragment is composed of three parts: 1) 5.7 kb proximal part, 2) the central, variable size D4Z4 repeat array, and 3) the distal part, usually 1.25 kb. The proximal portion has a sequence of DNA stainable by the probe p13E-11, which is commonly used to visualize the EcoRI fragment during southern blot. The name "p13E-11" reflects that it is a subclone of a DNA sequence designated as cosmid 13E during the human genome project. Sometimes D4Z4 repeat array deletions can include the p13E-11 binding site, warranting use of alternate probes. Considering that each D4Z4 repeat is 3.3 kb, and the EcoRI fragment contains 6.9 kb of DNA that is not part of the D4Z4 repeat array, the number of D4Z4 units can be calculated.

- D4Z4 repeats = (EcoRI length - 6.9) / 3.3

Alternative testing

1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-220px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg" decoding="async" width="220" height="310" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-330px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-440px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg 2x" data-file-width="1986" data-file-height="2795">

1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-220px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg" decoding="async" width="220" height="310" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-330px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif/lossy-page1-440px-FSHD_MRI_Asymmetrical_Muscle_Involvement.tif.jpg 2x" data-file-width="1986" data-file-height="2795"> When cost is prohibitive or a diagnosis of FSHD is not suspected as the cause of symptoms, patients and doctors may rely on one or more of the following tests, all of which are less sensitive and less specific than genetic testing.

- Creatine kinase (CK) blood level is often ordered when muscle damage is suspected. CK is an enzyme found in muscle, and it is released into the blood when muscles become damaged. However, CK levels are only mildly elevated, or even normal, in FSHD.

- Electromyogram (EMG) measures the electrical activity in the muscle. EMG shows nonspecific signs of muscle damage or irritability.

- Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) measures the how fast signals travel from one part of a nerve to another. The nerve signals are measured with surface electrodes (similar to those used for an electrocardiogram) or needle electrodes.

- Muscle biopsy involves surgical removal of a small piece of muscle, usually from the arm or leg. The biopsy is evaluated with a variety of biochemical tests. Biopsies from FSHD-affected muscles show nonspecific signs, such as presence of white blood cells and variation in muscle fiber size. This test is rarely indicated.

- Muscle MRI is sensitive for detecting muscle damage, even in paucisymptomatic cases. Because of the particular muscle involvement patterns of FSHD, MRI can help differentiate FSHD from other muscle diseases, directing molecular diagnosis.

Management

As of 2020, there is no cure for FSHD, and no pharmaceuticals have definitively proven effective for altering the disease course. Aerobic exercise has been shown to reduce chronic fatigue and decelerate fatty infiltration of muscle in FSHD. The American Academy of Neurology (ANN) recommends that people with FSHD engage in low-intensity aerobic exercise to promote energy levels, muscle health, and bone health. Moderate-intensity strength training appears to do no harm, although it hasn't been shown to be beneficial. Physical therapy can address specific symptoms; there is no standardized protocol for FSHD. Anecdotal reports suggest that appropriately applied kinesiology tape can reduce pain. Occupational therapy can be used for training in activities of daily living (ADLs) and to help adapt to new assistive devices. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to reduce chronic fatigue in FSHD, and it also decelerates fatty infiltration of muscle when directed towards increasing daily activity.

Braces are often used to address muscle weakness. Scapular bracing can improve scapular positioning, which improves shoulder function, although it is often deemed as ineffective or impractical. Ankle-foot orthoses can improve walking, balance, and quality of life.

Multiple medical tests can be done to detect complications. A dilated eye exam to look for retinal abnormalities is recommended in those newly diagnosed with FSHD. Those with large D4Z4 deletions should be referred to a retinal specialist for yearly exams. A hearing test should be done in individuals with early-onset FSHD, prior to starting school, or any other FSHD-affected individual with symptoms of hearing loss. Pulmonary function testing (PFT) should be done in those newly diagnosed to establish baseline pulmonary function. PFT should also be done recurrently for those with risks for or symptoms of pulmonary insufficiency.

Surgical intervention

Various manifestations of facial weakness are amenable to surgical correction. Upper eyelid gold implants have been used for those unable to close their eyes. Drooping lower lip has been addressed with plastic surgery. Select cases of foot drop can be surgically corrected with tendon transfer, such as the Bridle procedure. Severe scoliosis caused by FSHD can be corrected with spinal fusion.

Several procedures can address scapular winging, the best known being scapulothoracic fusion (arthrodesis), an orthopedic procedure that achieves bony fusion between the scapula and the ribs. It increases shoulder active range of motion, improves shoulder function, decreases pain, and improves cosmetic appearance. Active range of motion increases most in the setting of severe scapular winging with an unaffected deltoid muscle; however, passive range of motion decreases. Namely, the patient gains the ability to slowly flex and abduct their shoulders to 90+ degrees, but they lose the ability to "throw" their arm up to a full 180 degrees. A second procedure type is scapulopexy, which involves tethering the scapula to the ribs, vertebrae, or other scapula using tendon grafts, wire, or other means. Unlike the scapulothoracic fusion, no fusion between bones is achieved. Several types of scapulopexy exist, and outcomes are different for each. Compared to scapulothoracic fusions, scapulopexies are considered to be less invasive, but also more susceptible to long-term failure. An alternative treatment, not commonly done, is tendon transfer, which involves rearranging the attachments of muscles to bone. Examples include pectoralis major transfer and the Eden-Lange procedure.

- Scapular winging management

Kinesiology tape applied across the scapulas.

A cloth brace to hold the scapulas in retraction to reduce shoulder symptoms, such as collarbone pain.

Scapula-to-scapula scapulopexy, pre- and post-operation. The scapulas are tethered together with an Achilles tendon graft, holding them in a retracted position. In the right image, the rhomboid major muscles are easily visible.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of FSHD ranges from 1 in 8,333 to 1 in 15,000. The Netherlands reports a prevalence of 1 in 8,333, after accounting for the undiagnosed. The prevalence in the United States is commonly quoted as 1 in 15,000.

After genetic testing became possible in 1992, average prevalence was found to be around 1 in 20,000, a large increase compared to before 1992. However, 1 in 20,000 is likely an underestimation, since many with FSHD have mild symptoms and are never diagnosed, or they are siblings of affected individuals and never seek diagnosis.

Race and ethnicity have not been shown to affect FSHD incidence or severity.

Although the inheritance of FSHD shows no predilection for biological sex, the disease manifests less often in women, and even when it manifests in women, they on average are less severely affected than affected males. Estrogen has been suspected to be a protective factor that accounts for this discrepancy. One study found that estrogen reduced DUX4 activity. However, another study found no association between disease severity and lifetime estrogen exposure in females. The same study found that disease progression wasn't different through periods of hormonal changes, such as menarche, pregnancy, and menopause.

History

The first description of a person with FSHD in medical literature appears in an autopsy report by Jean Cruveilhier in 1852. In 1868, Duchenne published his seminal work on Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and as part of its differential was a description of FSHD. First in 1874, then with a more commonly cited publication in 1884, and again with pictures in 1885, the French physicians Louis Landouzy and Joseph Dejerine published details of the disease, recognizing it as a distinct clinical entity, and thus FSHD is sometimes referred to as Landouzy Dejerine disease. In their paper of 1886, Landouzy and Dejerine drew attention to the familial nature of the disorder and mentioned that four generations were affected in the kindred that they had investigated. Formal definition of FSHD's clinical features didn't occur until 1952 when a large Utah family with FSHD was studied. Beginning about 1980 an increasing interest in FSHD led to increased understanding of the great variability in the disease and a growing understanding of the genetic and pathophysiological complexities. By the late 1990s, researchers were finally beginning to understand the regions of chromosome 4 associated with FSHD.

Since the publication of the unifying theory in 2010, researchers continued to refine their understanding of DUX4. With increasing confidence in this work, researchers proposed the first a consensus view in 2014 of the pathophysiology of the disease and potential approaches to therapeutic intervention based on that model.

Over the years, FSHD has, at various times, been referred to as:

- facioscapulohumeral disease

- faciohumeroscapular

- Landouzy-Dejerine disease

- Landouzy-Dejerine syndrome

- Landouzy-Dejerine type of muscular dystrophy

- Erb-Landouzy-Dejerine syndrome

- Landouzy and Dejerine describe a form of childhood progressive muscle atrophy with a characteristic involvement of facial muscles and distinct from pseudohypertrophic (Duchenne’s MD) and spinal muscle atrophy in adults.

1886

- Landouzy and Dejerine describe progressive muscular atrophy of the scapulo-humeral type.

1950

- Tyler and Stephens study 1249 individuals from a single kindred with FSHD traced to a single ancestor and describe a typical Mendelian inheritance pattern with complete penetrance and highly variable expression. The term facioscapulohumeral dystrophy is introduced.

1982

- Padberg provides the first linkage studies to determine the genetic locus for FSHD in his seminal thesis "Facioscapulohumeral disease."

1987

- The complete sequence of the Dystrophin gene (Duchenne’s MD) is determined.

1991

- The genetic defect in FSHD is linked to a region (4q35) near the tip of the long arm of chromosome 4.

1992

- FSHD, in both familial and de novo cases, is found to be linked to a recombination event that reduces the size of 4q EcoR1 fragment to < 28 kb (50–300 kb normally).

1993

- 4q EcoR1 fragments are found to contain tandem arrangement of multiple 3.3-kb units (D4Z4), and FSHD is associated with the presence of < 11 D4Z4 units.

- A study of seven families with FSHD reveals evidence of genetic heterogeneity in FSHD.

1994

- The heterochromatic structure of 4q35 is recognized as a factor that may affect the expression of FSHD, possibly via position-effect variegation.

- DNA sequencing within D4Z4 units shows they contain an open reading frame corresponding to two homeobox domains, but investigators conclude that D4Z4 is unlikely to code for a functional transcript.

1995

- The terms FSHD1A and FSHD1B are introduced to describe 4q-linked and non-4q-linked forms of the disease.

1996

- FSHD Region Gene1 (FRG1) is discovered 100 kb proximal to D4Z4.

1998

- Monozygotic twins with vastly different clinical expression of FSHD are described.

1999

- Complete sequencing of 4q35 D4Z4 units reveals a promoter region located 149 bp 5' from the open reading frame for the two homeobox domains, indicating a gene that encodes a protein of 391 amino acid protein (later corrected to 424 aa), given the name DUX4.

2001

- Investigators assessed the methylation state (heterochromatin is more highly methylated than euchromatin) of DNA in 4q35 D4Z4. An examination of SmaI, MluI, SacII, and EagI restriction fragments from multiple cell types, including skeletal muscle, revealed no evidence for hypomethylation in cells from FSHD1 patients relative to D4Z4 from unaffected control cells or relative to homologous D4Z4 sites on chromosome 10. However, in all instances, D4Z4 from sperm was hypomethylated relative to D4Z4 from somatic tissues.

2002

- A polymorphic segment of 10 kb directly distal to D4Z4 is found to exist in two allelic forms, designated 4qA and 4qB. FSHD1 is associated solely with the 4qA allele.

- Three genes (FRG1, FRG2, ANT1) located in the region just centromeric to D4Z4 on chromosome 4 are found in isolated muscle cells from individuals with FSHD at levels 10 to 60 times greater than normal, showing a linkage between D4Z4 contractions and altered expression of 4q35 genes.

2003

- A further examination of DNA methylation in different 4q35 D4Z4 restriction fragments (BsaAI and FseI) showed significant hypomethylation at both sites for individuals with FSHD1, non-FSHD-expressing gene carriers, and individuals with phenotypic FSHD relative to unaffected controls.

2004

- Contraction of the D4Z4 region on the 4qB allele to < 38 kb does not cause FSHD.

2006

- Transgenic mice overexpressing FRG1 are shown to develop severe myopathy.

2007

- The DUX4 open reading frame is found to have been conserved in the genome of primates for over 100 million years, supporting the likelihood that it encodes a required protein.

- Researchers identify DUX4 mRNA in primary FSHD myoblasts and identify in D4Z4-transfected cells a DUX4 protein, the overexpression of which induces cell death.

- DUX4 mRNA and protein expression are reported to increase in myoblasts from FSHD patients, compared to unaffected controls. Stable DUX4 mRNA is transcribed only from the most distal D4Z4 unit, which uses an intron and a polyadenylation signal provided by the flanking pLAM region. DUX4 protein is identified as a transcription factor, and evidence suggests overexpression of DUX4 is linked to an increase in the target paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PITX1).

2009

- The terms FSHD1 and FSHD2 are introduced to describe D4Z4-deletion-linked and non-D4Z4-deletion-linked genetic forms, respectively. In FSHD1, hypomethylation is restricted to the short 4q allele, whereas FSHD2 is characterized by hypomethylation of both 4q and both 10q alleles.

- Splicing and cleavage of the terminal (most telomeric) 4q D4Z4 DUX4 transcript in primary myoblasts and fibroblasts from FSHD patients is found to result in the generation of multiple RNAs, including small noncoding RNAs, antisense RNAs and capped mRNAs as new candidates for the pathophysiology of FSHD.

2010

- A unifying genetic model of FSHD is established: D4Z4 contractions only cause FSHD when in the context of a 4qA allele due to stabilization of DUX4 RNA transcript, allowing DUX4 expression. Several organizations including The New York Times highlighted this research (See FSHD Society).

Dr. Francis Collins, who oversaw the first sequencing of the Human Genome with the National Institutes of Health stated:

“If we were thinking of a collection of the genome’s greatest hits, this would go on the list,”

Daniel Perez, co-founder of the FSHD Society, hailed the new findings saying:

"This is a long-sought explanation of the exact biological workings of [FSHD]”

The MDA stated that:

"Now, the hunt is on for which proteins or genetic instructions (RNA) cause the problem for muscle tissue in FSHD."

One of the report's co-authors, Silvère van der Maarel of the University of Leiden, stated that

“It is amazing to realize that a long and frustrating journey of almost two decades now culminates in the identification of a single small DNA variant that differs between patients and people without the disease. We finally have a target that we can go after.”

- DUX4 is found actively transcribed in skeletal muscle biopsies and primary myoblasts. FSHD-affected cells produce a full length transcript, DUX4-fl, whereas alternative splicing in unaffected individuals results in the production of a shorter, 3'-truncated transcript (DUX4-s). The low overall expression of both transcripts in muscle is attributed to relatively high expression in a small number of nuclei (~ 1 in 1000). Higher levels of DUX4 expression in human testis (~100 fold higher than skeletal muscle) suggest a developmental role for DUX4 in human development. Higher levels of DUX4-s (vs DUX4-fl) are shown to correlate with a greater degree of DUX-4 H3K9me3-methylation.

2012

- Some instances of FSHD2 are linked to mutations in the SMCHD1 gene on chromosome 18, and a genetic/mechanistic intersection of FSHD1 and FSHD2 is established.

- The prevalence of FSHD-like D4Z4 deletions on permissive alleles is significantly higher than the prevalence of FSHD in the general population