Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD), also referred to simply as Alzheimer's, is a neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and gradually worsens over time. It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems with language, disorientation (including easily getting lost), mood swings, loss of motivation, self-neglect, and behavioural issues. As a person's condition declines, they often withdraw from family and society. Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death. Although the speed of progression can vary, the typical life expectancy following diagnosis is three to nine years.

The cause of Alzheimer's disease is poorly understood. About 70% of the risk is believed to be inherited from a person's parents, with many genes usually involved. Other risk factors include a history of head injuries, depression, and hypertension. The disease process is associated with amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. A probable diagnosis is based on the history of the illness and cognitive testing with medical imaging and blood tests to rule out other possible causes. Initial symptoms are often mistaken for normal ageing. Examination of brain tissue is needed for a definite diagnosis. Mental and physical exercise, and avoiding obesity may decrease the risk of AD; however, evidence to support these recommendations is weak. There are no medications or supplements that have been shown to decrease risk.

No treatments stop or reverse its progression, though some may temporarily improve symptoms. Affected people increasingly rely on others for assistance, often placing a burden on the caregiver. The pressures can include social, psychological, physical, and economic elements. Exercise programs may be beneficial with respect to activities of daily living and can potentially improve outcomes. Behavioural problems or psychosis due to dementia are often treated with antipsychotics, but this is not usually recommended, as there is little benefit and an increased risk of early death.

As of 2015, there were approximately 29.8 million people worldwide with AD with about 50 million as of 2020. It most often begins in people over 65 years of age, although 4–5% of cases are early-onset Alzheimer's. It affects about 6% of people 65 years and older. In 2015, all forms of dementia resulted in about 1.9 million deaths. The disease is named after German psychiatrist and pathologist Alois Alzheimer, who first described it in 1906. In developed countries, AD is one of the most financially costly diseases.

Signs and symptoms

- Effects of ageing on memory but not AD

- Forgetting things occasionally

- Misplacing items sometimes

- Minor short-term memory loss

- Not remembering exact details

- Early stage Alzheimer's

- Not remembering episodes of forgetfulness

- Forgets names of family or friends

- Changes may only be noticed by close friends or relatives

- Some confusion in situations outside the familiar

- Middle stage Alzheimer's

- Greater difficulty remembering recently learned information

- Deepening confusion in many circumstances

- Problems with sleep

- Trouble determining their location

- Late stage Alzheimer's

- Poor ability to think

- Problems speaking

- Repeats same conversations

- More abusive, anxious, or paranoid

The disease course is divided into four stages, with a progressive pattern of cognitive and functional impairment.

29.jpg/220px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg" decoding="async" width="220" height="474" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg/330px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg/440px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg 2x" data-file-width="1284" data-file-height="2766">

29.jpg/220px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg" decoding="async" width="220" height="474" class="thumbimage" srcset="//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg/330px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg/440px-Alzheimer%E2%80%99s_Disease%2C_Spreads_through_the_Brain_%2824524716351%29.jpg 2x" data-file-width="1284" data-file-height="2766"> Pre-dementia

The first symptoms are often mistakenly attributed to ageing or stress. Detailed neuropsychological testing can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfills the clinical criteria for diagnosis of AD. These early symptoms can affect the most complex activities of daily living. The most noticeable deficit is short term memory loss, which shows up as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts and inability to acquire new information.

Subtle problems with the executive functions of attentiveness, planning, flexibility, and abstract thinking, or impairments in semantic memory (memory of meanings, and concept relationships) can also be symptomatic of the early stages of AD. Apathy and depression can be seen at this stage, with apathy remaining as the most persistent symptom throughout the course of the disease. The preclinical stage of the disease has also been termed mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This is often found to be a transitional stage between normal ageing and dementia. MCI can present with a variety of symptoms, and when memory loss is the predominant symptom, it is termed "amnestic MCI" and is frequently seen as a prodromal stage of Alzheimer's disease.

Early

In people with AD, the increasing impairment of learning and memory eventually leads to a definitive diagnosis. In a small percentage, difficulties with language, executive functions, perception (agnosia), or execution of movements (apraxia) are more prominent than memory problems. AD does not affect all memory capacities equally. Older memories of the person's life (episodic memory), facts learned (semantic memory), and implicit memory (the memory of the body on how to do things, such as using a fork to eat or how to drink from a glass) are affected to a lesser degree than new facts or memories.

Language problems are mainly characterised by a shrinking vocabulary and decreased word fluency, leading to a general impoverishment of oral and written language. In this stage, the person with Alzheimer's is usually capable of communicating basic ideas adequately. While performing fine motor tasks such as writing, drawing, or dressing, certain movement coordination and planning difficulties (apraxia) may be present, but they are commonly unnoticed. As the disease progresses, people with AD can often continue to perform many tasks independently, but may need assistance or supervision with the most cognitively demanding activities.

Moderate

Progressive deterioration eventually hinders independence, with subjects being unable to perform most common activities of daily living. Speech difficulties become evident due to an inability to recall vocabulary, which leads to frequent incorrect word substitutions (paraphasias). Reading and writing skills are also progressively lost. Complex motor sequences become less coordinated as time passes and AD progresses, so the risk of falling increases. During this phase, memory problems worsen, and the person may fail to recognise close relatives. Long-term memory, which was previously intact, becomes impaired.

Behavioural and neuropsychiatric changes become more prevalent. Common manifestations are wandering, irritability and labile affect, leading to crying, outbursts of unpremeditated aggression, or resistance to caregiving. Sundowning can also appear. Approximately 30% of people with AD develop illusionary misidentifications and other delusional symptoms. Subjects also lose insight of their disease process and limitations (anosognosia). Urinary incontinence can develop. These symptoms create stress for relatives and carers, which can be reduced by moving the person from home care to other long-term care facilities.

Advanced

During the final stages, the patient is completely dependent upon caregivers. Language is reduced to simple phrases or even single words, eventually leading to complete loss of speech. Despite the loss of verbal language abilities, people can often understand and return emotional signals. Although aggressiveness can still be present, extreme apathy and exhaustion are much more common symptoms. People with Alzheimer's disease will ultimately not be able to perform even the simplest tasks independently; muscle mass and mobility deteriorates to the point where they are bedridden and unable to feed themselves. The cause of death is usually an external factor, such as infection of pressure ulcers or pneumonia, not the disease itself.

Causes

Alzheimer's disease is believed to occur when abnormal amounts of proteins, amyloids and possibly tau proteins, form in the brain and begin to encroach upon the organ's cells. The resultant plaque disrupts normal function and chemistry, and leads to a significant deficit of neurotransmitters, resulting in a progressive loss of brain function. As for why these protein 'malfunctions' occur in the first place, the ultimate cause is poorly understood, and subject to ongoing research and speculation.

The cause for most Alzheimer's cases is still mostly unknown except for 1% to 5% of cases where genetic differences have been identified. Several competing hypotheses exist trying to explain the cause of the disease.

Genetic

The genetic heritability of Alzheimer's disease (and memory components thereof), based on reviews of twin and family studies, ranges from 49% to 79%. Around 0.1% of the cases are familial forms of autosomal (not sex-linked) dominant inheritance, which have an onset before age 65. This form of the disease is known as early onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Most of autosomal dominant familial AD can be attributed to mutations in one of three genes: those encoding amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilins PSEN1 and PSEN2. Most mutations in the APP and presenilin genes increase the production of a small protein called Aβ42, which is the main component of senile plaques. Some of the mutations merely alter the ratio between Aβ42 and the other major forms—particularly Aβ40—without increasing Aβ42 levels. Two other genes associated with autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease are ABCA7 and SORL1.

Most cases of Alzheimer's disease do not exhibit autosomal-dominant inheritance and are termed sporadic AD, in which environmental and genetic differences may act as risk factors. The best known genetic risk factor is the inheritance of the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE). Between 40 and 80% of people with AD possess at least one APOEε4 allele. The APOEε4 allele increases the risk of the disease by three times in heterozygotes and by 15 times in homozygotes. Like many human diseases, environmental effects and genetic modifiers result in incomplete penetrance. For example, certain Nigerian populations do not show the relationship between dose of APOEε4 and incidence or age-of-onset for Alzheimer's disease seen in other human populations. Early attempts to screen up to 400 candidate genes for association with late-onset sporadic AD (LOAD) resulted in a low yield. More recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found 19 areas in genes that appear to affect the risk. These genes include: CASS4, CELF1, FERMT2, HLA-DRB5, INPP5D, MEF2C, NME8, PTK2B, SORL1, ZCWPW1, SLC24A4, CLU, PICALM, CR1, BIN1, MS4A, ABCA7, EPHA1, and CD2AP.

Alleles in the TREM2 gene have been associated with a 3 to 5 times higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. A suggested mechanism of action is that in some variants in TREM2, white blood cells in the brain are no longer able to control the amount of beta amyloid present. Many single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with Alzheimer's, with a 2018 study adding 30 SNPs by differentiating AD into 6 categories, including memory, language, visuospatial, and executive functioning.

Cholinergic hypothesis

The oldest hypothesis, on which most currently available drug therapies are based, is the cholinergic hypothesis, which proposes that AD is caused by reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The cholinergic hypothesis has not maintained widespread support, largely because medications intended to treat acetylcholine deficiency have not been very effective.

Amyloid hypothesis

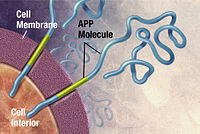

In 1991, the amyloid hypothesis postulated that extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) deposits are the fundamental cause of the disease. Support for this postulate comes from the location of the gene for the amyloid precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21, together with the fact that people with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) who have an extra gene copy almost universally exhibit at least the earliest symptoms of AD by 40 years of age. Also, a specific isoform of apolipoprotein, APOE4, is a major genetic risk factor for AD. While apolipoproteins enhance the breakdown of beta amyloid, some isoforms are not very effective at this task (such as APOE4), leading to excess amyloid buildup in the brain. Further evidence comes from the finding that transgenic mice that express a mutant form of the human APP gene develop fibrillar amyloid plaques and Alzheimer's-like brain pathology with spatial learning deficits.

An experimental vaccine was found to clear the amyloid plaques in early human trials, but it did not have any significant effect on dementia. Researchers have been led to suspect non-plaque Aβ oligomers (aggregates of many monomers) as the primary pathogenic form of Aβ. These toxic oligomers, also referred to as amyloid-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs), bind to a surface receptor on neurons and change the structure of the synapse, thereby disrupting neuronal communication. One receptor for Aβ oligomers may be the prion protein, the same protein that has been linked to mad cow disease and the related human condition, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, thus potentially linking the underlying mechanism of these neurodegenerative disorders with that of Alzheimer's disease.

In 2009, this hypothesis was updated, suggesting that a close relative of the beta-amyloid protein, and not necessarily the beta-amyloid itself, may be a major culprit in the disease. The hypothesis holds that an amyloid-related mechanism that prunes neuronal connections in the brain in the fast-growth phase of early life may be triggered by ageing-related processes in later life to cause the neuronal withering of Alzheimer's disease. N-APP, a fragment of APP from the peptide's N-terminus, is adjacent to beta-amyloid and is cleaved from APP by one of the same enzymes. N-APP triggers the self-destruct pathway by binding to a neuronal receptor called death receptor 6 (DR6, also known as TNFRSF21). DR6 is highly expressed in the human brain regions most affected by Alzheimer's, so it is possible that the N-APP/DR6 pathway might be hijacked in the ageing brain to cause damage. In this model, beta-amyloid plays a complementary role, by depressing synaptic function.

Osaka mutation

A Japanese pedigree of familial Alzheimer's disease was found to be associated with a deletion mutation of codon 693 of APP. This mutation and its association with Alzheimer's disease was first reported in 2008. This mutation is known as the Osaka mutation. Only homozygotes with this mutation develop Alzheimer's disease. This mutation accelerates Aβ oligomerization but the proteins do not form amyloid fibrils suggesting that it is the Aβ oligomerization rather than the fibrils that may be the cause of this disease. Mice expressing this mutation have all usual pathologies of Alzheimer's disease.

Tau hypothesis

The tau hypothesis proposes that tau protein abnormalities initiate the disease cascade. In this model, hyperphosphorylated tau begins to pair with other threads of tau. Eventually, they form neurofibrillary tangles inside nerve cell bodies. When this occurs, the microtubules disintegrate, destroying the structure of the cell's cytoskeleton which collapses the neuron's transport system. This may result first in malfunctions in biochemical communication between neurons and later in the death of the cells.

Other hypotheses

An inflammatory hypothesis is that AD is caused by a self-perpetuating progressive inflammation in the brain culminating in neurodegeneration. A possible role of chronic periodontal infection and the gut microbiota has been suggested.

A neurovascular hypothesis stating that poor functioning of the blood–brain barrier may be involved has been proposed. Spirochete infections have also been linked to dementia.

The cellular homeostasis of biometals such as ionic copper, iron, and zinc is disrupted in AD, though it remains unclear whether this is produced by or causes the changes in proteins. These ions affect and are affected by tau, APP, and APOE, and their dysregulation may cause oxidative stress that may contribute to the pathology. The quality of some of these studies has been criticised, and the link remains controversial. The majority of researchers do not support a causal connection with aluminium.

Smoking is a significant AD risk factor. Systemic markers of the innate immune system are risk factors for late-onset AD.

There is tentative evidence that exposure to air pollution may be a contributing factor to the development of Alzheimer's disease.

One hypothesis posits that dysfunction of oligodendrocytes and their associated myelin during aging contributes to axon damage, which then causes amyloid production and tau hyper-phosphorylation as a side effect.

Retrogenesis is a medical hypothesis about the development and progress of Alzheimer's disease proposed by Barry Reisberg in the 1980s. The hypothesis is that just as the fetus goes through a process of neurodevelopment beginning with neurulation and ending with myelination, the brains of people with AD go through a reverse neurodegeneration process starting with demyelination and death of axons (white matter) and ending with the death of grey matter. Likewise the hypothesis is, that as infants go through states of cognitive development, people with AD go through the reverse process of progressive cognitive impairment. Reisberg developed the caregiving assessment tool known as "FAST" (Functional Assessment Staging Tool) which he says allows those caring for people with AD to identify the stages of disease progression and that provides advice about the kind of care needed at each stage.

The association with celiac disease is unclear, with a 2019 study finding no increase in dementia overall in those with CD, while a 2018 review found an association with several types of dementia including AD.

Pathophysiology

Neuropathology

Alzheimer's disease is characterised by loss of neurons and synapses in the cerebral cortex and certain subcortical regions. This loss results in gross atrophy of the affected regions, including degeneration in the temporal lobe and parietal lobe, and parts of the frontal cortex and cingulate gyrus. Degeneration is also present in brainstem nuclei like the locus coeruleus. Studies using MRI and PET have documented reductions in the size of specific brain regions in people with AD as they progressed from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease, and in comparison with similar images from healthy older adults.

Both Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are clearly visible by microscopy in brains of those afflicted by AD, especially in the hippocampus. Plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid peptide and cellular material outside and around neurons. Tangles (neurofibrillary tangles) are aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau which has become hyperphosphorylated and accumulate inside the cells themselves. Although many older individuals develop some plaques and tangles as a consequence of ageing, the brains of people with AD have a greater number of them in specific brain regions such as the temporal lobe. Lewy bodies are not rare in the brains of people with AD.

Biochemistry

Alzheimer's disease has been identified as a protein misfolding disease (proteopathy), caused by plaque accumulation of abnormally folded amyloid beta protein and tau protein in the brain. Plaques are made up of small peptides, 39–43 amino acids in length, called amyloid beta (Aβ). Aβ is a fragment from the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP). APP is a transmembrane protein that penetrates through the neuron's membrane. APP is critical to neuron growth, survival, and post-injury repair. In Alzheimer's disease, gamma secretase and beta secretase act together in a proteolytic process which causes APP to be divided into smaller fragments. One of these fragments gives rise to fibrils of amyloid beta, which then form clumps that deposit outside neurons in dense formations known as senile plaques.

AD is also considered a tauopathy due to abnormal aggregation of the tau protein. Every neuron has a cytoskeleton, an internal support structure partly made up of structures called microtubules. These microtubules act like tracks, guiding nutrients and molecules from the body of the cell to the ends of the axon and back. A protein called tau stabilises the microtubules when phosphorylated, and is therefore called a microtubule-associated protein. In AD, tau undergoes chemical changes, becoming hyperphosphorylated; it then begins to pair with other threads, creating neurofibrillary tangles and disintegrating the neuron's transport system. Pathogenic tau can also cause neuronal death through transposable element dysregulation.

Disease mechanism

Exactly how disturbances of production and aggregation of the beta-amyloid peptide give rise to the pathology of AD is not known. The amyloid hypothesis traditionally points to the accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides as the central event triggering neuron degeneration. Accumulation of aggregated amyloid fibrils, which are believed to be the toxic form of the protein responsible for disrupting the cell's calcium ion homeostasis, induces programmed cell death (apoptosis). It is also known that Aβ selectively builds up in the mitochondria in the cells of Alzheimer's-affected brains, and it also inhibits certain enzyme functions and the utilisation of glucose by neurons.

Various inflammatory processes and cytokines may also have a role in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Inflammation is a general marker of tissue damage in any disease, and may be either secondary to tissue damage in AD or a marker of an immunological response. There is increasing evidence of a strong interaction between the neurons and the immunological mechanisms in the brain. Obesity and systemic inflammation may interfere with immunological processes which promote disease progression.

Alterations in the distribution of different neurotrophic factors and in the expression of their receptors such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been described in AD.

Diagnosis

Alzheimer's disease is usually diagnosed based on the person's medical history, history from relatives, and behavioural observations. The presence of characteristic neurological and neuropsychological features and the absence of alternative conditions is supportive. Advanced medical imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to help exclude other cerebral pathology or subtypes of dementia. Moreover, it may predict conversion from prodromal stages (mild cognitive impairment) to Alzheimer's disease.

Assessment of intellectual functioning including memory testing can further characterise the state of the disease. Medical organisations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardise the diagnostic process for practising physicians. The diagnosis can be confirmed with very high accuracy post-mortem when brain material is available and can be examined histologically.

Criteria

The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA, now known as the Alzheimer's Association) established the most commonly used NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria for diagnosis in 1984, extensively updated in 2007. These criteria require that the presence of cognitive impairment, and a suspected dementia syndrome, be confirmed by neuropsychological testing for a clinical diagnosis of possible or probable AD. A histopathologic confirmation including a microscopic examination of brain tissue is required for a definitive diagnosis. Good statistical reliability and validity have been shown between the diagnostic criteria and definitive histopathological confirmation. Eight intellectual domains are most commonly impaired in AD—memory, language, perceptual skills, attention, motor skills, orientation, problem solving and executive functional abilities. These domains are equivalent to the NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) published by the American Psychiatric Association.

Techniques

Neuropsychological tests such as the mini–mental state examination (MMSE) are widely used to evaluate the cognitive impairments needed for diagnosis. More comprehensive test arrays are necessary for high reliability of results, particularly in the earliest stages of the disease. Neurological examination in early AD will usually provide normal results, except for obvious cognitive impairment, which may not differ from that resulting from other diseases processes, including other causes of dementia.

Further neurological examinations are crucial in the differential diagnosis of AD and other diseases. Interviews with family members are also utilised in the assessment of the disease. Caregivers can supply important information on the daily living abilities, as well as on the decrease, over time, of the person's mental function. A caregiver's viewpoint is particularly important, since a person with AD is commonly unaware of his own deficits. Many times, families also have difficulties in the detection of initial dementia symptoms and may not communicate accurate information to a physician.

Supplemental testing provides extra information on some features of the disease or is used to rule out other diagnoses. Blood tests can identify other causes for dementia than AD—causes which may, in rare cases, be reversible. It is common to perform thyroid function tests, assess B12, rule out syphilis, rule out metabolic problems (including tests for kidney function, electrolyte levels and for diabetes), assess levels of heavy metals (e.g., lead, mercury) and anaemia. (It is also necessary to rule out delirium).

Psychological tests for depression are employed, since depression can either be concurrent with AD (see Depression of Alzheimer disease), an early sign of cognitive impairment, or even the cause.

Due to low accuracy, the C-PIB-PET scan is not recommended to be used as an early diagnostic tool or for predicting the development of Alzheimer's disease when people show signs of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The use of 18F-FDG PET scans, as a single test, to identify people who may develop Alzheimer's disease is also not supported by evidence.

Prevention

There is no definitive evidence to support that any particular measure is effective in preventing AD. Global studies of measures to prevent or delay the onset of AD have often produced inconsistent results. Epidemiological studies have proposed relationships between certain modifiable factors, such as diet, cardiovascular risk, pharmaceutical products, or intellectual activities, among others, and a population's likelihood of developing AD. Only further research, including clinical trials, will reveal whether these factors can help to prevent AD.

Medication

Cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, are associated with a higher risk of onset and worsened course of AD. Blood pressure medications may decrease the risk. Statins, which lower cholesterol however, have not been effective in preventing or improving the course of the disease.

Long-term usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were thought in 2007 to be associated with a reduced likelihood of developing AD. Evidence also suggested the notion that NSAIDs could reduce inflammation related to amyloid plaques, but trials were suspended due to high adverse events. No prevention trial has been completed. They do not appear to be useful as a treatment, but as of 2011[update] were thought to be candidates as presymptomatic preventives. Hormone replacement therapy in menopause, although previously used, may increase the risk of dementia.

Lifestyle

People who engage in intellectual activities such as reading books (but not newspapers), playing board games, completing crossword puzzles, playing musical instruments, or regular social interaction show a reduced risk for Alzheimer's disease. This is compatible with the cognitive reserve theory, which states that some life experiences result in more efficient neural functioning providing the individual a cognitive reserve that delays the onset of dementia manifestations. Education delays the onset of AD syndrome without changing the duration of the disease. Learning a second language even later in life seems to delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease. Physical activity is also associated with a reduced risk of AD. Physical exercise is associated with decreased rate of dementia. Physical exercise is also effective in reducing symptom severity in those with Alzheimer's disease.

Diet

People who maintain a healthy, Japanese, or Mediterranean diet have a reduced risk of AD. A Mediterranean diet may improve outcomes in those with the disease. Those who eat a diet high in saturated fats and simple carbohydrates (mono- and disaccharide) have a higher risk. The Mediterranean diet's beneficial cardiovascular effect has been proposed as the mechanism of action.

Conclusions on dietary components have at times been difficult to ascertain as results have differed between population-based studies and randomised controlled trials. There is limited evidence that light to moderate use of alcohol, particularly red wine, is associated with lower risk of AD. There is tentative evidence that caffeine may be protective. A number of foods high in flavonoids such as cocoa, red wine, and tea may decrease the risk of AD.

Reviews on the use of vitamins and minerals have not found enough consistent evidence to recommend them. This includes vitamin A, C, the alpha-tocopherol form of vitamin E, selenium, zinc, and folic acid with or without vitamin B12. Evidence from one randomized controlled trial indicated that the alpha-tocopherol form of vitamin E may slow cognitive decline, this evidence was judged to be "moderate" in quality. Trials examining folic acid (B9) and other B vitamins failed to show any significant association with cognitive decline. Omega-3 fatty acid supplements from plants and fish, and dietary docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), do not appear to benefit people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.

Curcumin as of 2010[update] had not shown benefit in people even though there is tentative evidence in animals. There was inconsistent and unconvincing evidence that ginkgo has any positive effect on cognitive impairment and dementia. As of 2008[update] there was no concrete evidence that cannabinoids are effective in improving the symptoms of AD or dementia; however, some research into endocannabinoids looked promising.

Management

There is no cure for Alzheimer's disease; available treatments offer relatively small symptomatic benefit but remain palliative in nature. Current treatments can be divided into pharmaceutical, psychosocial and caregiving.

Medications

Five medications are currently used to treat the cognitive problems of AD: four are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (tacrine, rivastigmine, galantamine and donepezil) and the other (memantine) is an NMDA receptor antagonist. The benefit from their use is small. No medication has been clearly shown to delay or halt the progression of the disease.

Reduction in the activity of the cholinergic neurons is a well-known feature of Alzheimer's disease. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are employed to reduce the rate at which acetylcholine (ACh) is broken down, thereby increasing the concentration of ACh in the brain and combating the loss of ACh caused by the death of cholinergic neurons. There is evidence for the efficacy of these medications in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease, and some evidence for their use in the advanced stage. The use of these drugs in mild cognitive impairment has not shown any effect in a delay of the onset of AD. The most common side effects are nausea and vomiting, both of which are linked to cholinergic excess. These side effects arise in approximately 10–20% of users, are mild to moderate in severity, and can be managed by slowly adjusting medication doses. Less common secondary effects include muscle cramps, decreased heart rate (bradycardia), decreased appetite and weight, and increased gastric acid production.

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter of the nervous system, although excessive amounts in the brain can lead to cell death through a process called excitotoxicity which consists of the overstimulation of glutamate receptors. Excitotoxicity occurs not only in Alzheimer's disease, but also in other neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. Memantine is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist first used as an anti-influenza agent. It acts on the glutamatergic system by blocking NMDA receptors and inhibiting their overstimulation by glutamate. Memantine has been shown to have a small benefit in the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Reported adverse events with memantine are infrequent and mild, including hallucinations, confusion, dizziness, headache and fatigue. The combination of memantine and donepezil has been shown to be "of statistically significant but clinically marginal effectiveness".

Atypical antipsychotics are modestly useful in reducing aggression and psychosis in people with Alzheimer's disease, but their advantages are offset by serious adverse effects, such as stroke, movement difficulties or cognitive decline. When used in the long-term, they have been shown to associate with increased mortality. Stopping antipsychotic use in this group of people appears to be safe.

Psychosocial intervention

Psychosocial interventions are used as an adjunct to pharmaceutical treatment and can be classified within behaviour-, emotion-, cognition- or stimulation-oriented approaches. Research on efficacy is unavailable and rarely specific to AD, focusing instead on dementia in general.

Behavioural interventions attempt to identify and reduce the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviours. This approach has not shown success in improving overall functioning, but can help to reduce some specific problem behaviours, such as incontinence. There is a lack of high quality data on the effectiveness of these techniques in other behaviour problems such as wandering. Music therapy is effective in reducing behavioural and psychological symptoms.

Emotion-oriented interventions include reminiscence therapy, validation therapy, supportive psychotherapy, sensory integration, also called snoezelen, and simulated presence therapy. A Cochrane review has found no evidence that this is effective. Supportive psychotherapy has received little or no formal scientific study, but some clinicians find it useful in helping mildly impaired people adjust to their illness. Reminiscence therapy (RT) involves the discussion of past experiences individually or in group, many times with the aid of photographs, household items, music and sound recordings, or other familiar items from the past. A 2018 review of the effectiveness of RT found that effects were inconsistent, small in size and of doubtful clinical significance, and varied by setting. Simulated presence therapy (SPT) is based on attachment theories and involves playing a recording with voices of the closest relatives of the person with Alzheimer's disease. There is partial evidence indicating that SPT may reduce challenging behaviours. Finally, validation therapy is based on acceptance of the reality and personal truth of another's experience, while sensory integration is based on exercises aimed to stimulate senses. There is no evidence to support the usefulness of these therapies.

The aim of cognition-oriented treatments, which include reality orientation and cognitive retraining, is the reduction of cognitive deficits. Reality orientation consists in the presentation of information about time, place or person to ease the understanding of the person about its surroundings and his or her place in them. On the other hand, cognitive retraining tries to improve impaired capacities by exercitation of mental abilities. Both have shown some efficacy improving cognitive capacities, although in some studies these effects were transient and negative effects, such as frustration, have also been reported.

Stimulation-oriented treatments include art, music and pet therapies, exercise, and any other kind of recreational activities. Stimulation has modest support for improving behaviour, mood, and, to a lesser extent, function. Nevertheless, as important as these effects are, the main support for the use of stimulation therapies is the change in the person's routine.

Caregiving

Since Alzheimer's has no cure